July 11, 2007

Lessons of Indigo Prophecy, part 1

I remember my avatar murdering a stranger — and there was nothing I could do to stop it. Then another couple of my avatars came in to investigate the crime scene. A large black bird watched it all happen.

Yes, that’s right, recently I’ve been thinking about Indigo Prophecy (aka Fahrenheit, outside the U.S.). I realize it’s not exactly a new release, but games are not fruit, either. And I think there are some useful lessons to draw from this ambitious, flawed 2005 release from David Cage and Quantic Dream.

I’m interested here, primarily, in thinking about the relationship between gameplay and story. Cage’s ambitions in this area have been discussed by Andrew in his more timely GTxA post on Indigo Prophecy. Cage’s goals might be considered a less-risky version of the “interactive drama” vision that guides Façade: the gameplay can change the story in significant ways, but the system ensures the story retains an essential shape and pacing. In other words, the story becomes playable, rather than something that happens between moments of play.

That, however, is not what I want to talk about here. Rather, I want to discuss the fit between gameplay and story. Most games I think about in terms of story haven’t brought such issues to the fore. Consider, for example, Jordan Mechner’s Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time. Here a non-playable story does what one would expect — motivating the action, providing a context for play, etc. The story requires a swashbuckling prince to move through a ruined palace, toward a particular point, fighting monsters along the way. The gameplay, as one might expect, is focused on platforming and combat. PoP:SoT is better than average in some important ways (e.g., plot twists that also force changes in play) but I’ll take its kind of story/gameplay fit as a baseline here.

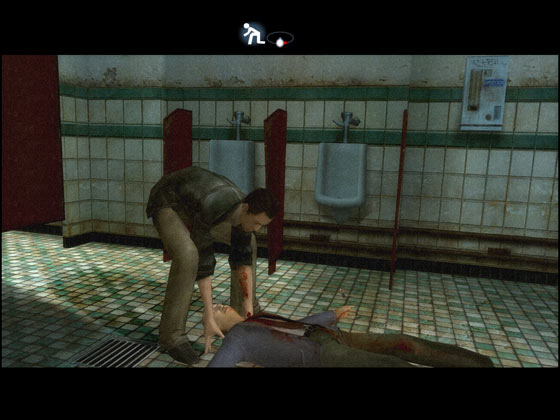

This brings us to the story and gameplay of Indigo Prophecy (which I’ll try to cover with minimal spoilers). The game begins with a ritual murder, which is investigated both by the confused murderer and the police. As players we begin as the murderer, just after the crime, and the initial gameplay involves hiding evidence and escaping the scene. This is pretty creepy and effective, managing to teach us IP’s control scheme for simple physical actions (in the image above, the icon on top shows how to move the analog stick to drag the body) while maintaining an atmosphere more like a noir film than a training level.

Next we play the police. This took me by surprise. I was already rooting for Lucas Kane, the semi-innocent murderer I’d played in the first scene, and I wasn’t sure if I should deliberately play the police (Carla Valenti and Tyler Miles) poorly. But the game gave positive feedback for playing them well — finding evidence, questioning the witness with sensitivity — so I did that. Being in the flow of the story seemed to help me choose better conversation options (represented using short prompts, selected between with the same analog stick movements as physical actions) which I took as a good sign. Also, I had to choose between conversation options quickly, before a timer forced the default, and this made the dialogue trees feel a little more like conversations unfolding in time. At this point I was definitely getting into Indigo Prophecy.

But in the next scene, playing the murderer waking in his apartment, troubles began to brew. These very same troubles would boil over dramatically, making a rather spectacular mess, before I finished the game. There are four particular troubles that I’d like to discuss.

First, I was encouraged to do a lot of irrelevant fiddling. For example, there are a number of things that can be done with Lucas’s computer in this scene — but none impact the game structure and most distract from the story. Many future scenes would provide many opportunities for such fiddling.

Second, I started to feel that unwelcome, mundane elements of The Sims had been dropped into my previously dark, mysterious game. While I wanted to get on with the story, the game encourages taking Lucas to the toilet to urinate and to the shower to get clean. You’d think an “interactive drama” (a phrase Cage has used) would elide these undramatic activities. Instead, a mental health meter for each character encourages players to constantly skew characters from the paths of their investigations to play music (on the stereo, on the guitar), drink (milk, coffee, wine), rest (on the couch, on the bed), and so on.

Third, this scene also introduced the Tarot cards hidden throughout the game. I found this scene’s card floating in one of the kitchen cupboards. These cards provide incentives to slow the characters’ investigations further by checking every out of the way space in the game. In most scenes you can count on a tarot card being in some place in the opposite direction from the part of the space in which the story continues. Since this sort of traversal of space involves no gameplay challenge (in most instances) and runs counter to the story’s movement, I found this puzzling.

Fourth, and most importantly, this scene introduced me to IP’s biggest source of gameplay challenge: directional-input challenges. This is the topic I will take up in my next post.

July 11th, 2007 at 9:11 pm

I know you know this, but Cage’s inclusion of toilets and drinking water and everything else was in a bid for making the game appear like it’s documenting a real life, rather than a story. It didn’t work so well, especially with the SPOILERSPOILERSPOILERSPOILERRscrewed up endingSPOILERSPOILERSPOILERSPOILER.

You could play without the diversions, but things took time to happen, giving you plenty of time to fiddle. The sudden death syndrome this created was really, really not fun.

Oh hey, I’m depressed, I’ll take some pills. Mmm. Pills.

What’s in the cupboard? Whiskey. Awesome, I’ll calm down. Drink the whiskey.

Collapse. Dead.

“I knew I shouldn’t have mixed alcohol and pain killers” (or words to that effect).

If I’d known, I wouldn’t have done it!

Leaving the player to his/her own devices and then letting them commit non-obvious methods of suicide is plain frustrating.

I also found the dichotomy of playing the police and Kane frustrating. Like you said, you’ve bonded with Kane… and now you’re being asked to ruin him. Doing badly with the police was once mooted as a way of getting Kane off the hook, obviously that didn’t reach the final game because the story is completely on rails until the multiple-endings. And doing badly with the police results in you being chastised and your officer feeling depressed.

It all hints towards a greater game and a greater narrative in Cage’s vision that never reached fruition, either by running out of money, will or the publisher kicking it out the door. That the first half of the game was so much better than the last half seems to indicate this as well.

July 11th, 2007 at 10:48 pm

I played this game a couple of years ago and found it both remarkable and dreadful.

The best feature by far, which Noah has already touched on, is the tension created by alternating between playing the murderer and the cops. I think this is really a novel creation and a very effective one. It should be lauded as a success for interactive story. It has created a dramatic effect which I think would not be nearly so so effective in another form. Playing the characters forces you to sympathise with them and take on their goals, in a way that just reading about or watching them can never do. The sense of conflict that I felt was very real, and it is played out well, up until a major confrontation scene between the two sides.

The other thing I thought worked well was the premonitions the murderer has at the beginning of certain scenes. They work well as both foreboding and also as directions of how to play out the scene without too much floundering (which is otherwise a much too common feature of adventure games). They made it possible to have tense time-limited scenes, without creating a “learning-by-dying” scenario. This didn’t always work for me (I still ‘died’ many times in the army base scene) but for the most part it was effective.

The worst feature by far was the ending. This was just a failure of imagination on the part of the writers. What started out as an intriguing mystery was resolved into a blandly generic fantasy ending. Oh and the sex scene was gross. Ick. Ick. Ick.

To pre-empt what Noah is going to say about the “game” elements – I found them to be an entertaining challenge, but one that distracted from the story. To play the scenes I had to concentrate on the lights, which meant that I could give little attention to the actual scene that I was supposedly controlling. Often I got successfully to the end of a challenge only to wonder exactly what my character had been doing while I has been pressing the keys.

It should also be said that (to use James Wallis’ terms) this is a “story-telling” game, not a “story-making” game. The author has a particular story to tell and the player’s input into it is minor. Essentially the player just has to complete each scene in order to drive the story forward. There is some freedom within the scene, but the only major departures from the main storyline are failure (losing the game).

In all, while this game doesn’t really depart very far from traditional story-game mechanics, it does show how these mechanics can be used to good effect to produce a story-telling experience which is uniquely interactive. The story is told through active player participation, which (at least in some scenes) gives it a potency that a passive telling would struggle to achieve. To find this in a commercially published work is, I think, a milestone for the interactive narrative movement.

July 13th, 2007 at 1:39 am

Glad others have some thoughts about Indigo Prophecy / Farenhiet. I think it’s quite interesting, if definitely flawed.

Chris, Malcolm, one curious thing to me is that you two reacted so differently to playing both Lucas and the police. Personally, I think it worked up until a certain point — when the game seemed to break one of its own cardinal rules. I’ll get into that in my next post.

Also, what you both say about the beginning being better than the end is something Cage has definitely talked about. For example, in his Game Developer postmortem he agrees that the end has plot problems (I don’t think that’s too spoilery a thing to say) and he also says:

Here we are, three players who were hooked by the first hour and utterly turned off by the last one.

Malcolm, you’re definitely right about Lucas’s premonitions. They created urgency, and gave additional information, in a way that made sense. Also, they made the 24-style split screen operate as more than a gimmick. As for the sex scenes, I guess this is a case where I should be glad for my home country’s prudishness? They were cut from the release in the U.S.

As for IP being a “story-telling” game, that’s true. But I think it’s important to point out — as you do — how much of the gameplay that works is actually determining the micro level of how the story plays out in a particular scene. It’s not like a game with combat sequences which, if successful, always lead to the same canned dialogue. Instead it’s a game with some pretty successful uses of a timed dialogue engine, in which the same scene can have different tones and reveal different information depending on how you play. I think that’s what makes Cage’s use of the term “interactive drama” something other than a joke, even if the macro-level story has very little variation.

As for the lights, I’ll post my thought on them soon. A key point for the lessons I want to draw here.

PS — Chris, I killed myself with the wiskey and pills as well. What is it about us that we didn’t know better? :)

July 13th, 2007 at 3:33 am

When Lucas picks pills, he actually reads the inscription, saying “Don’t mix with alcohol” (I played european version though). Didn’t stop me from drinking whiskey to see what would happen =)

July 16th, 2007 at 12:38 pm

I personally loved the controls in this game- my manual dexterity has always made for awful targeting in FPS games. But my hand-eye coordination and sense of timing are pretty good, so I felt vindicated for a change that I was handling the controls better than my BF, which was a huge swap. It also kind of helped that I had previously been passably good at DDR.

That being said, I played the PC version using an xbox-like controller, and the ‘balancing’ control challenges drove me crazy. I think I spent quite a while sending Carla into a catatonic state in the basement. But I eventually got the hang of it.

I really liked the character switching, because it became less about helping the protagonist ‘win’, and more about getting the story to unfold- all three characters were essentially pursuing the same goal of solving the mystery, but each bringing their own skills and knowledge to the table. Kind of an interesting change.

Am I the only one that decided not to mix pills with alcohol?

July 17th, 2007 at 12:50 am

[…] would a game of two-handed Simon mean more… Yes, it’s time to continue the discussion of Indigo Prophesy (aka Fahrenheit) and in particular wh […]

July 17th, 2007 at 2:37 am

BEGIN (yucky) SPOILER

There were two. One with Kane’s ex-girlfriend early on in the game, which was largely unremarkable. The later one, between Kane and Carla was awful. It took place in the subways _after_ Kane has “died”. Carla even remarks on his skin being cold. Ew.

END

Another thing that really bugged me in this game was the temperature thing. The early game made it seem much more important than it turned out to be. And the stupidest thing: The non-US version of the game was called “Fahrenheit”, but then they converted the on-screen thermometer to Celcius.

July 17th, 2007 at 1:46 pm

Ah, I think maybe the U.S. version has abbreviated/altered versions. That yucky thing you mention with skin temperature is definitely in there…

July 17th, 2007 at 3:51 pm

Malcolm, I think the first sex scene had the dubious honour of being the first interactive sex scene in a mainstream game. I can certainly remember sex scenes in earlier games… but not interactive ones.

July 18th, 2007 at 8:41 pm

Ah yes, I forgot that it was “interactive”.

August 31st, 2007 at 5:37 pm

when this game over it done what else is going to go on with the game called indigo prophecy i would love to know what happends nexts

October 9th, 2007 at 11:21 pm

[…]

A lot has been mentioned on here about Indigo Prophecy already – by Andrew, by Noah (1 2), and by commenters who followed up those posts. I want to add two th […]