July 17, 2007

Lessons of Indigo Prophecy, part 2

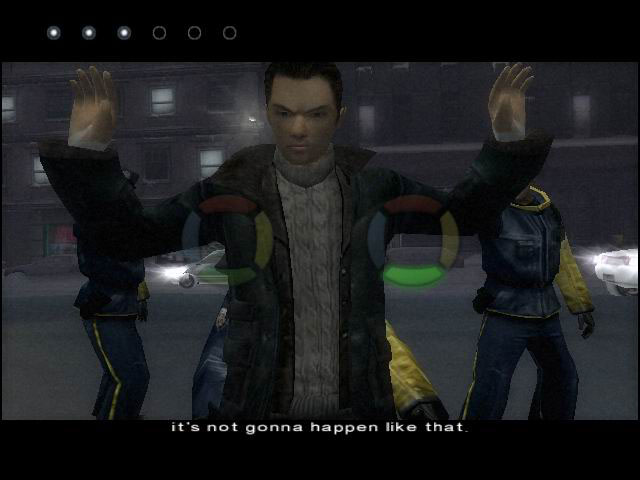

When those cops got the drop on me, I knew it was the decisive moment, when it all came together, the turning point of my life. Never would a game of two-handed Simon mean more…

Yes, it’s time to continue the discussion of Indigo Prophecy (aka Fahrenheit) and in particular what it can teach us about the fit between gameplay and story. Last week I started out by saying how engrossing and different I found the initial scenes — first covering up for a murder my avatar (Lucas Kane) committed, then investigating it (as my two police officer avatars, Carla Valenti and Tyler Miles), with good atmosphere and a nice take on dialogue trees. Then, in the next scene, things started to go wrong: irrelevant fiddling encouraged by the environment, mundane activities encouraged by the mental health meter, navigation away from the site of action encouraged by hidden Tarot cards, and one special issue left for this post: the directional-input challenges.

As pictured above, directional-input challenges superimpose two circles over the fictional world’s image on the screen. Each circle is composed of four differently-colored segments — up and down, left and right, resembling nothing so much as the game Simon. And the gameplay, it turns out, is quite similar. Quadrants of the circle light up, in different orders, but (rather than having to remember and repeat whole sequences) the challenge for the player is to follow along as quickly as possible, moving the two analog sticks in directions corresponding to the most recent lights while watching for the next.

During that first scene in the apartment, successfully completing the challenge results in channeling a premonition (of the sort mentioned in Malcolm’s comment). In other parts of IP this same gameplay is used to determine success at concentration during a guided meditation, boxing, basketball, magical combat, dodging oncoming cars while running down the street, dancing, dealing with the cops pictured at the top of this post, and so on. As this list may suggest, many of IP’s gameplay challenges having nothing to do with the story. We’re left to wonder why our intrepid police take time off for boxing and basketball at this point in their investigations. More importantly, making boxing and basketball things we must successfully play through to continue the game is as puzzling a choice of focus for Indigo Prophecy as the simulations of personal grooming.

Less obviously, this method of gameplay does something unfortunate to the game’s fictional setting: it makes it superfluous. In Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time (PoP) we pay attention to the world depicted on the screen even if our sole interest is in efficient play — because it depicts the player character’s position relative structures and combatants, helps us decide what actions to take next, and gives feedback about which actions were successful. The fictional world of IP, on the other hand, is separated from its directional challenge gameplay. Not only does the world provide no help in playing, but during intense play the fictional world and events within it become a distraction for which no attention can be spared. In later sections of the game I have only a vague notion of what happened, fictionally, during moments of action. My attention was entirely on two rapidly-blinking colored circles and the movements of my thumbsticks.

In other words, this “interactive drama” got my undivided attention at its most mundane moments — and got none at what should have been its climactic action high points. While some complain that the use of cut scenes relegates story to an interruption of gameplay, surely this is better than placing it in simultaneous competition with challenging gameplay. After all, in such a competition gameplay will always win, because the player simply can’t continue in the game without successful play.

On a different note, in the comments on my previous post I was interested to see the differing views (of Chris and Malcolm) about playing both Lucas and the police. At first I was quite surprised by this turn in the game — but IP gave clear feedback that I should try to succeed at every task, whoever I was playing, so I quickly adjusted to this unfamiliar game scenario.

[Begin Spoiler]

Which only made me more disappointed when this was later rescinded. Later in the game we play Lucas as he is being questioned by one of the officers. During the questioning he is plagued by monstrous visions. In an earlier scene these same visions appeared and could only be survived by playing the directional-input game well. During this questioning, however, I played the directional-input game perfectly, repeatedly, only to have each success result in the police being more suspicious of Lucas and his mental health deteriorating. I played through this scene repeatedly. Each time, I played so many directional challenges so well that I ended up in an insane asylum.

I had to resort to a game guide to tell me that the only successful route through this part of IP is to intentionally fail at the directional input game, apparently as a simulation of ignoring the visions. At that point, the game had broken the main rule that had allowed me to enter into its unusual arrangement. In the wake of that frustration and its resolution, most of what was left of my emotional and narrative engagement dissipated. I played through the rest out of professional curiosity.

[End Spoiler]

Of course, while it may not be obvious at this point, I write all this with motivations other than complaint. I think the failures of IP illuminate issues that may be harder to perceive when playing games that integrate story and gameplay more successfully. Here are some lessons I think we can glean from Indigo Prophecy:

First, if story is important to a game, do not highlight events through gameplay that are distractions from the story. In IP we see this at scales ranging from the high-level structure (non-optional sections of the game that are unrelated to the story, such as the boxing and basketball sequences) to the moment-by-moment (encouraging small gameplay decisions that run counter to the story, such as pointless meandering in search of Tarot cards).

Second, conversely, choose things to make playable that are related to the story. When it happens, this is some of what works best in IP, such as the hiding and finding of evidence in the first two scenes.

Third, make the game’s fictional world a resource for successful play, rather than putting the two in competition. In IP, this works well with dialogue tree gameplay and poorly with directional input gameplay.

Fourth, if you have an innovation that is tied to your narrative goals (such as IP’s requirement to play characters with conflicting interests) help your audience build up a new play model quickly (such as IP’s encouragement to succeed at every task presented, even if some work against what was accomplished in earlier tasks) and then don’t violate this.

Of course, all of this could be seen as just the story-specific version of common advice about games in general: Players focus on what they can play — and especially on what the game structures encourage them to play — so these elements should be the very ones that strengthen the experience the designers want to create. The designers may want to create a moody, mysterious experience; a chaotic, free-for-all experience; an open, exploratory experience; or a tense, action-packed experience. In any case, what the game makes playable should be the elements that contribute to such an experience. The opening of Indigo Prophecy was largely like this. I await the story-focused game that continues as strongly as IP started.

July 17th, 2007 at 1:05 am

Oh — Megan’s comment didn’t make it out of the moderation queue until after I’d written the above. She offers a counter-argument to what I say about the directional-input challenges, one which makes the obvious (so how’d I miss it?) connection to DDR.

July 17th, 2007 at 1:37 am

Makes me glad that I never bought the game.

The design review made me tangentially think of a list of “rules for choices” that I’ve been gradually expanding: http://www.mxac.com.au/drt/Choices3.htm .

I wonder if an equivalent could be created regarding story/game integration. For example: The sub-games should be chosen to enhance the story, to pull the player into the experience, not merely as a way to slow their progress through the story. Making me play basketball doesn’t make me feel more like a cop. Making me play basketball with DDR footsteps via mouse doesn’t make me feel like I’m playing basketball.

July 17th, 2007 at 1:56 am

haha, you got stuck in the same place i did! (around a year ago) i would love to see more story focused games like IP in the future. i hold high hopes for mass effect on xbox360 for this reason. too bad i don’t on a 360

July 17th, 2007 at 4:11 am

I liked the game although it was riddled with flaws, story-holes and shortcomings. I got a sense, for example, that a few large portions towards the end of the game had to be cut during production.

I wrote a piece on the game a couple of months back that try to highlight some other aspects of the game. You can read it here: http://www.sicher.org/2006/11/15/the-split-personality-of-fahrenheit-indigo-prophecy

July 17th, 2007 at 5:26 am

>First, if story is important to a game, do not highlight events through gameplay that are distractions from the story

I am not sure… On the other hand, the story take place in a world, which exist independently from the story, and I think that giving to the player proofs of that, through events and facts not directly related to the story, is somewhat necessary to suspension of disbelief.

Personally, I liked the boxing or basket game, or some of the more mundane part (getting up, having an argument with girlfriend, having a drink with neighbour etc…) because of its uselessness…

However I agree about the tarot cards, completely useless, and the, huh, suboptimal ‘directional-input challenges’ which drive the attention out of the world and/or the story. It seems they felt that ‘action-style’ gameplay was a necessary evil, even if it do not integrate seamlessly with the world/story.

And the last 1/4 of the scenario was awful, almost ridiculous. But it’s one of the few big game which actually experience smth about story and gameplay. Unlike The longest journey for example, which play exactly the same as any point and click adventure game from the last 20 years…

July 17th, 2007 at 9:24 am

I like your formulation (from the beginning of part 1 of this discussion) of good narrative in games: “the story becomes playable, rather than something that happens between moments of play.”

This pairs well with your complaint about the “Simon” game-interface, which enforces an absolute separation of gameplay from story.

In the former case, the story is relegated to mere interruption of the game, as you say; in the latter, story and gameplay occur on irreconcilable levels:

“While some complain that the use of cut scenes relegates story to an interruption of gameplay, surely this is better than placing it in simultaneous competition with challenging gameplay.”

(We’re preferring the former because, though both make the story all but superfluous, interrupted is still better than disrupted.)

My question is this: given these design-dangers, how does one go about matching gameplay and story, so that they neither interrupt or disrupt, but both cooperate simultaneously?

Within the convention of arcade game-design (a propos Simon) where gameplay (interacting with the engine) and story (the narrative significance of the interactions) are distinct, their cooperation is produced, if it is produced, by creative interpretation of game events. In other words, it’s a question of presentation.

As a proud member of the Allied forces, you’re not shooting polygons — well, you are, but what you’re *really* doing is hunting those damn Coalition fighters. And this one is a slippery bugger!

In a space-shooter, or in a FPS, say, you reach a point — whew that was close! — where the mind is working on two levels simultaneously. There’s a part that’s interpreting the action as meaningful, and a part that is overseeing the manual gymnastics with the controller. The former is passively aware of the latter, but in its free time it’s constructing narratives, often ex nihil, but it can be guided by for instance decent backstory, or audio narration, or again creative interpretation.

Whether it’s a training mission with a bunch of targets, or “the base is under attack and you’ve got to hold them off!” with a bunch of enemies — the material gameplay may be exactly the same. It simply depends, at least for the most part, upon how you present it to the player.

I guess the point boils down to this: what you *are* doing (shooting polygons or whatever) — that’s what must be reinterpreted, given significance. You can’t superimpose something unrelated on top of it. If you can’t tell a story with Simon, by reinterpreting the gameplay in an interesting way, then you picked the wrong game.

July 17th, 2007 at 11:52 am

I agree with the complaints about the game superimposing a Simon game over cutscenes. Compare “Indigo Prophecy” game with “God of War” and “Resident Evil 4”, for instance. These two games also feature Simon games, albeit more glorified ones.

In “Indigo Prophecy”, I too experienced that my focus on the Simon game almost completely blocked out the storytelling that took place in the background. That was a bad thing for the narrative scenes but not so much for the action-scenes (more on that below).

In “God of War”, the problem does not occur. The cutscenes you experience (during boss battles) does not convey story but action alone, so it’s not crucial that you seep in everything that happens in detail. For these kinds of scenes it actually feels like it’s good that you don’t pay too much attention to details. When you focus is on spotting pop-up HUD elements you are less keen on spotting glitches in the scenes so your memory of the fights will probably exceed reality. Some of the action-oriented scenes in “Indigo” (the basketball game, for instance) actually worked like that for me.

In “Resident Evil 4”, the cutscenes contained some narrative, but I found myself paying great attention to exactly what went on. There, you never knew when the game would force you to interact. The Simon moments were very sparse, but you could often guess when they were about to appear by the action. In that game, the interaction moment kept me alert. I paid attention and the Simon-game never got in the way.

Still, I think that these are all pretty dull game design choices. To me, this is almost “Dragon’s Lair” all over again… :)

July 17th, 2007 at 12:34 pm

Mike, I think the game is cheap enough now that it might be worth buying just for the first couple scenes. Unless you’re the kind of player that can’t stop until they get to the end, in which case you might want to weigh the choice more carefully.

Your “Choices III” is an interesting document. Have you used it to analyze any particular games or game designs?

Perhaps something similar could be developed for story/game integration — but a central question is the role the story plays in the game. For IP the story is presented as the center of things. This sort of project probably should follow different guidelines than even RPGs like Oblivion which, while they have (small and large) stories as major elements, have such developed fictional worlds because they’re also encouraging a certain amount of sandbox-style gameplay.

PetitPiteux, this leads into my thoughts about your comment. I think giving players an independently-existing fictional world is one thing. For example, I largely agree with this statement of Cage’s from his Game Developer postmortem:

The parts of this scene that work are exactly the ones that are about Tyler’s personal life, especially his interactions with his wife. The ones that don’t work are the ones “based on the traditional mechanics of video games” (e.g., will this improve my mental health meter?). If Cage wanted to make IP a sandbox or simulation game, he didn’t go far enough. If he wanted to make an interactive drama, which is what I suspect, then the quantification elements should have gone away and (if possible) everything playable should have deepened our sense of his history, relationships, and role in the story.

The same goes for Lucas. When he wakes up in his apartment for the first time, before the premonition, I don’t care a thing about whether he takes a shower. It would have been more effective to leave me, the player, pacing back and forth with nothing to do. But better than that would have been to only place playavble objects around my apartment (like the television and family photo) that, when played, deepen my sense of the fiction.

Okay, I must go for a bit, but I’ll write more in response to the excellent comments soon…

July 17th, 2007 at 1:51 pm

breslin, I’ve been thinking along the lines of a three-level model.

At one level, which is basically an area of active research, the story itself is playable. How you play alters the shape of the story — on the macro level, micro level, or both. Hitting both is, of course, the Facade goal.

At a level that can be shipped for Christmas, the story is fixed, or has a small number of options — but gameplay is a close fit with the story. This is the Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time level, and I think it might also be the more successful one you’re describing in your comment. You’re playing actions that have significance within the story, not playing the story itself.

At the “this is a problem” level, the story and gameplay are detached from each other — or even in competition. Part of what makes Indigo Prophecy worth discussing is that some elements are at this level, while others get as close to the playable (micro) story level as anything I’ve seen commercially.

Would you agree with a basic model like this?

Mikael, I have to sign off again, but I’ll try to address some of your thoughts soon.

July 17th, 2007 at 5:23 pm

Noah: “If he wanted to make an interactive drama, which is what I suspect, then the quantification elements should have gone away and (if possible) everything playable should have deepened our sense of his history, relationships, and role in the story.”

Exactly. This is why the banal basketball game seemed to exist only to pad the game out. The whole framing of the event was to settle a score about some money the player had never even taken. I learnt nothing of Tyler or his history, just that he plays basketball, regardless of the freezing temperatures outside. I was able to take away far more from Tyler when he was waking up and getting dressed, which is one of the best scenes in the game.

I loathed the “Simon Says” games. QTE (quick time events) are used by game designers to express actions that cannot be properly enacted otherwise. Shenmue is a good usage of QTE, fighting mobsters with skill and precision, creating a vision of Ryu as an agile street fighter that was otherwise unattainable. Shenmue II also had the nonsense “hey, actually DON’T press it this time! But I’ll let you work it out for yourself!” QTE. I don’t know what would drive designers to do this; other than some horrible realisation that, actually, QTEs aren’t that varied.

The only times in Fahrenheit when they made sense was during Cage’s descents into madness, where the surrounding environment was falling apart so quickly that a QTE didn’t feel like it was pulling you out of the game world. I don’t need to play Simon Says to shoot hoops. Some of the button-mashing at the end of the game was so obscene that I honestly wanted to complete the game just out of spite (see: rooftop fight).

Basing so much of the game around that mechanic smacks as a knee-jerk reaction to the commercial failure of the point-and-click adventure; that players need some sort of frustrating reflex game in order to feel properly immersed. I remember the tutorial at the beginning, where Cage asks plays to “feel” themselves opening the door. This was the only usage of the analogue sticks that even came close to making sense.

I purchased the first-person shooter FEAR over the weekend. The narrative in the game is a pretty light touch, but it gives just enough to allow the player to create their own narrative, even when they have absolutely no ability to affect the story. Maybe a bit like breslin was shooting at, everything I did was significant to me (open door->slow motion->fill enemies with shotgun lead->cackle triumphantly) and enough to make me feel like I am writing the story, when of course it’s completely on-rails. I find it very hard to describe why, I think it’s because the story is not delivered in a gameplay->cut-scene mechanic. The little girl on the cover appears in the game at random, but quite frequent, intervals, but never for very long. I feel like I am discovering something the game doesn’t want me to know, through my dogged determination to kill everything in my path. It’s a melding of gameplay and narrative which is very hard to describe, and I am sure was not created by design and just a lucky coincidence, but it is pretty much the opposite of the way Fahrenheit approached things, light-handed, unobtrusive, natural. I’m filling in the sizeable blanks of the story myself. I hear it is about $20 in the US now.

July 17th, 2007 at 5:25 pm

Your three-tier model can very broadly characterize successes and failures, and it comments upon the current state-of-the-art.

Your statements about the “‘this is a problem’ level” (story in interruption, or story in non-relation) are useful for figuring out why certain designs don’t work, and by extension why other designs should be preferable.

Hopefully my comments about the successful match of story and gameplay illuminate not only how arcade games can have good stories (I was limiting myself to this only), but how “the narrative presentation of the material game structure” is essential to (or, equivalent to) the marriage of game and story. (So hopefully you won’t relegate my thoughts to the second tier only.)

==

Of course I’m making some simplifications: I’ve described a situation where we have a given game structure, and a designer comes along and creatively presents it; he receives a sort-of game manifold and creatively interprets and presents each element as storywise significant. What really happens in game design is not this neat two-stage affair, but something circular, where story and structure evolve simultaneously. Some germ of significance invariably comes before anything is put into code; there has to be a goal before there can be a design. Then as development proceeds, the game structure and the story/meaning mutually inform one another.

(One might well challenge whether structure and story can be properly understood to be two different things, except in those situations where the disjunct is the direct cause for the failure of the game (e.g., “Simon”-driven narrative).)

July 17th, 2007 at 6:09 pm

Noah wrote: Mike, I think the game is cheap enough now that it might be worth buying just for the first couple scenes. Unless you’re the kind of player that can’t stop until they get to the end, in which case you might want to weigh the choice more carefully. Your “Choices III” is an interesting document. Have you used it to analyze any particular games or game designs?

I have, but I haven’t put the analysis all in one place. (It’s scattered around may of the other articles I’ve put up. I know I’ve commented about choice w/regards to Oblivion, NWN2, AC2, WoW, EQ2.) Speaking of bargain bins, I picked up Broken Sword, the Angel of Death, to try it. I’ve only gotten through the first small bit and was thinking about writing an article about how it fails as far “choice” in most respects. But I haven’t had the time or inclination.

July 19th, 2007 at 4:25 pm

Actually, with that scene where you’re being questioned and the Simon Says game gives you visions that make the cops more suspicious: if your mental health starts out high enough, you can actually “pass” all the Simon games and keep playing through. That’s usually what I try and do, since I’m stubborn, and I think it fits the character better :)

I agree with everything else you were saying though. A lot of the storyline got lost behind the Simon wheels, especially the frenetically paced ones.

July 23rd, 2007 at 6:35 pm

I feel that this game (even though flawed) is really detailed ’cause this is the only game that can have die from pills and drinking and that there is at least a decent story unlike BLACK which for me was a waste of my money and that there was at least some creativity and that even at a few parts the game wasn’t repetive and sure I died a few times but I don’t cry about to me this game maybe deserves a 3.5 out of 5.

P.S. who really doesn’t know that drinking and popping pills can be fatal?

August 20th, 2007 at 7:13 pm

I’ve only played the first 5 minutes of IP, but have played through the entire Longest Journey – derided justifiably in an earlier comment for being like every other adventure game. What really struck me about Longest Journey though, was something akin to Cage’s ‘revelation’ about the waking up scene in IP. In Journey, you start off in your run down apartment, have a chat with your neighbour in the lobby below, then head off to your shift at the cafe. You have conversations with your good friends, who tell you about yourself. These early scenes are meant to be introductory – and informative tutorial (both in terms of gameplay and backstory) before you head off to the ‘real adventure’. But after playing through dozens of hours of fantastical worlds, overly eccentric characters and cutesy companions, this ‘intro’ was by far the most successful. Part of it was perhaps cultural – Being a young New Zealander I could identify with the small apartment and catching up with friends at a cafe. Part of it was realism – I forgave the graphics because it gave a good-enough impression of a real world scene, as opposed to a fantasy landscape with no real-world counterpart. Perhaps a conflict slowly interrupting a realistic daily rhythm would be a better first step in IF/gamedesign – rather than our usual cast of globe-trotting heroines and slug spewing hulks.

October 9th, 2007 at 11:22 pm

[…] A lot has been mentioned on here about Indigo Prophecy already – by Andrew, by Noah (1 2), and by commenters who followed up those posts. I want to add two thin […]